Here we go, The Big One. If you’ve played only one game featured here, it’s extremely likely to have been Slay the Spire. If you have enjoyed almost any other game in this subgenre since its release, it likely owes inspiration (a little more than just ‘inspiration’, in some cases) to Slay the Spire… or at least the nerve to take the plunge in bringing something similar to market following its success. Indeed, this is the roguelike deck-builder’s Super Mario Bros. or Doom moment: others of its kind existed before it, and by certain criteria it has been surpassed, but here is a perfect storm of great vision and execution that guarantees its place in gaming history.

Slay the Spire was released on Steam Early Access on November 15th, 2017 by American dev team Mega Crit (incidentally in the news recently for coming out against Unity’s ludicrous per-install engine usage fee). With the majority of its core gameplay locked in, the game was given regular bug and feature patches up until January 23rd, 2019, at which point it was released for computer platforms. Far and away the most financially and critically successful game we are likely to ever look at here, it is now available for most modern console platforms and mobile. It now even exists in physical board game form… surely the greatest sign that you’ve ‘made it’ as a, er, video game.

Premise and Gameplay

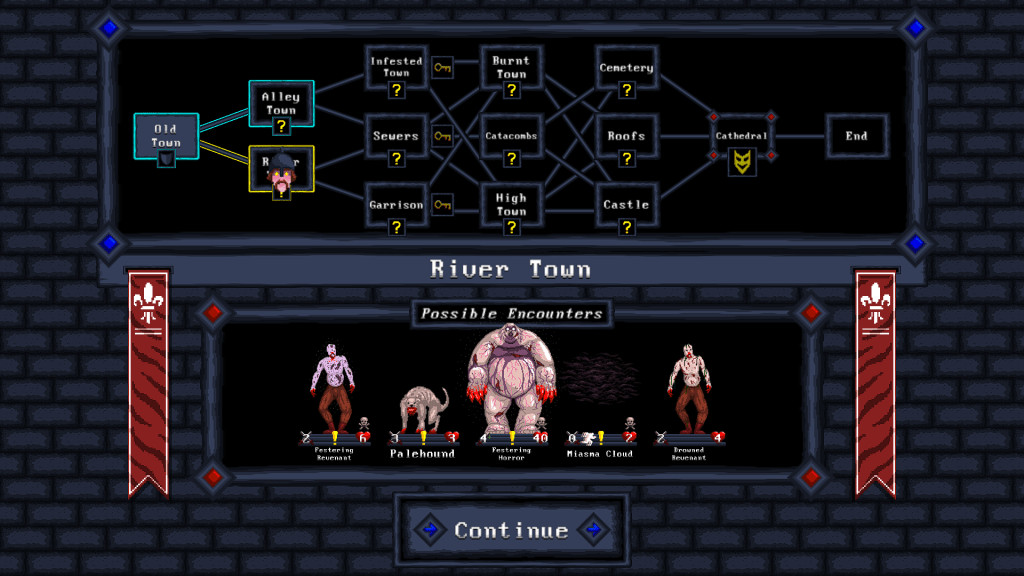

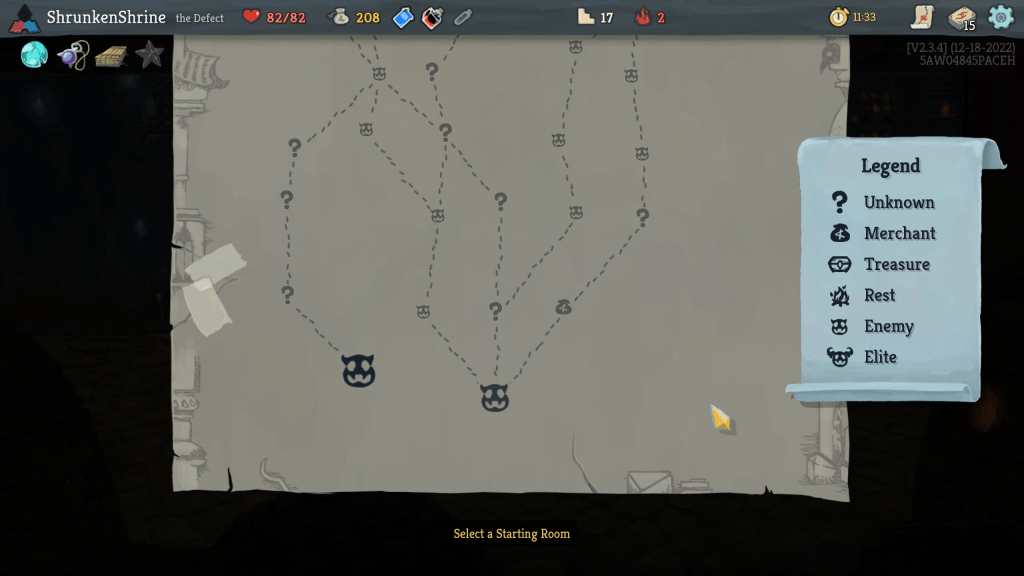

Your first run will start the exact same as your thousandth. Pick one of four character classes (the latter three are unlocked over time) and away you go to see Neow, a whale-like creature that guards the spire entrance and offers you a choice of blessings, such as raising your maximum health or upgrading one of your cards at random. Your run to reach the spire’s top is split into three acts, with each ending with a boss fight. Your paths to these bosses branch, offering a variety of scenarios. There are midboss battles (here called ‘elites’, a term that seems to have stuck for other such fights in roguelike deck-builders), shops, rest areas that allow you to heal or upgrade cards, random events that may help or hinder, and the like. Some of these are signposted well in advance of you reaching them, while others are randomised, so you are able to look ahead and plot whatever path to the boss you feel may be the most beneficial. You may know you have an elite fight coming up soon, but you won’t know exactly what enemy you’ll be facing, so you may want to choose an alternate (if less rewarding branch) where possible.

We’ve already seen earlier games with both more choice and diversity in their character classes, but StS’ Ironclad, Silent, Defect and Watcher are so tightly designed and well-executed that they are genre all-timers. (I mean, bias notwithstanding… I’m writing this wearing my shirt that features all of them, aren’t I.) The Ironclad is a high-risk, high-reward fighter option, often committing to high-damage builds that often jeopardise their own health. The Silent offers more of a health-whittling, death-by-a-thousand-cuts approach. These are certainly the two that you’ll be wanting to wrap your head around the basic run flow with, but the other two aren’t that much more impenetrable – they just have greater complexity and depth.

The Defect and the Watcher, who were added later after initial early access release, are surprisingly unique and deserve more detail. The former is a robot that can stockpile ice, electric, or dark energy to either provide or block chip damage every turn, or spend it all at once in order to strike or avoid decisive blows. The latter, my personal favourite, is a monk who can switch in and out of three different stances – Calm, Wrath, and Divinity. Calm allows you to shore up card-playing energy (think Magic mana). Slipping into Wrath forces you to deal and receive double damage, so making sure you have cards in hand that take you in and out of it before the turn passes to the enemy is vital. Divinity grants you an extra 3 energy to play cards with *and* lets you deal triple damage without the fear of double-damage that comes with Wrath, but takes far longer to reach than the other two states. Indeed, all of these playstyles are so unlike one another that it almost feels like you’re playing a different game, but for none of them to feel even remotely inferior to any other (besides whatever your personal preferences are) is incredible.

Randomised Elements

Compared even to other games that came before it, StS actually feels a lot less random, and I think this has actually helped it endure in the long run. You are likely to come across certain enemies almost every run, but because your deck build will have changed, you are forced to approach them in new ways. Another thing is that most of the classes only have three or so main ‘builds’ (several variations and derivatives are possible depending on circumstances). The Silent, for example, is likely to be stacking poison on their foes or drawing and playing many as many low-damage shivs as possible. As such, you are better able to form builds earlier in runs. I think this has actually added to the game’s longevity with streamers and speedrunners. The curve of learning what your enemies and cards are capable of doing is gentle and engaging, and even masters of the game who seemingly know every ramification of every scenario like the back of their hand keep coming back for more with self-imposed challenges and a healthy modding scene.

This nicely leads me into the game’s capacity to add difficulty modifiers, called ‘Ascensions’. Completing a run with the first Ascension active (which simply adds more elite battles) unlocks the next Ascension (regular enemies deal greater damage). The wrinkle is that these stack upon one another, all the way up to Ascension 20, by which point you’ll be laboring under all manner of handicaps, such as decreased maximum HP, limited inventory slots, or mandatory unplayable cards cluttering your hand. There are people out there who are capable of beating the game at ‘A20’ with a starting deck of only eight mid-tier cards or speedrunning it in 5 minutes. None of these feel like poor design, either. Like many RPGs (and unlike competitive CCGs), working out ways to break the game over your knee is simply another valid way of enjoying it, if you’re into that. Make no mistake though, you’d have to be really bloody good.

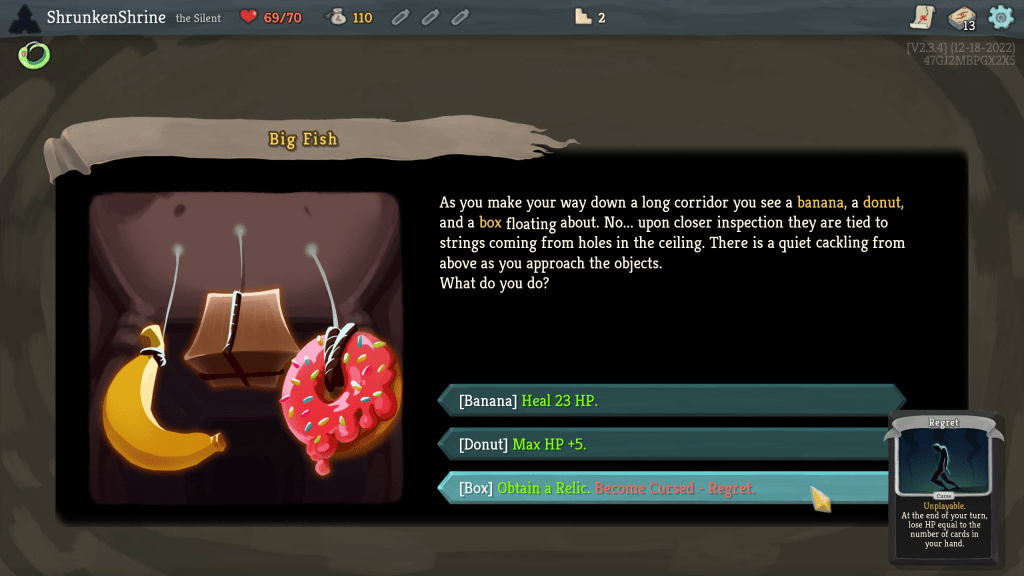

I’ve heard it said that at their core, a video game’s enjoyment factor can be boiled down to the quality and frequency of meaningful decisions you can make during your time with it. I find that a tad reductive, but it must be said that pretty much everything you do in StS is a meaningful decision that comes with a tradeoff. Do I drink this potion now or later? Which of these boss rewards should I take? A surprising way you can bring this game to life is to grab a friend (not even necessarily one who knows how to play) and try to ‘co-op’ a run. Revel in how it suddenly takes either of you ages to work up the nerve to actually commit to a play as you argue the merits of every playable card in your hand and come closer to understanding the tightness of the design. Marvel at how situations you’d mindlessly click through and potentially misplay when alone suddenly need you to crack out the whiteboard to justify the potential consequences a turn or two from now. Complexity does not always equate to depth, and depth does not always equate to fun. Slay the Spire isn’t the most complex or deep game we’ll ever look at here, but I contend it always stays fun.

Presentation

Slay the Spire was never a knockout in the looks and sound department (excellent character design aside), but it oozes with a premium Flash-era charm with its gently-animated enemies and backgrounds. There isn’t exactly what I’d call lore to it, but the way it’s been designed gestures toward the notion that there’s a lot more going on in this place than is explained. Who are these hook-wielding cultists who dress as birds? What happens to our brave heroes after slaying the spire? You won’t get any answers, but you probably won’t want any, you’ll be too absorbed in the game itself.

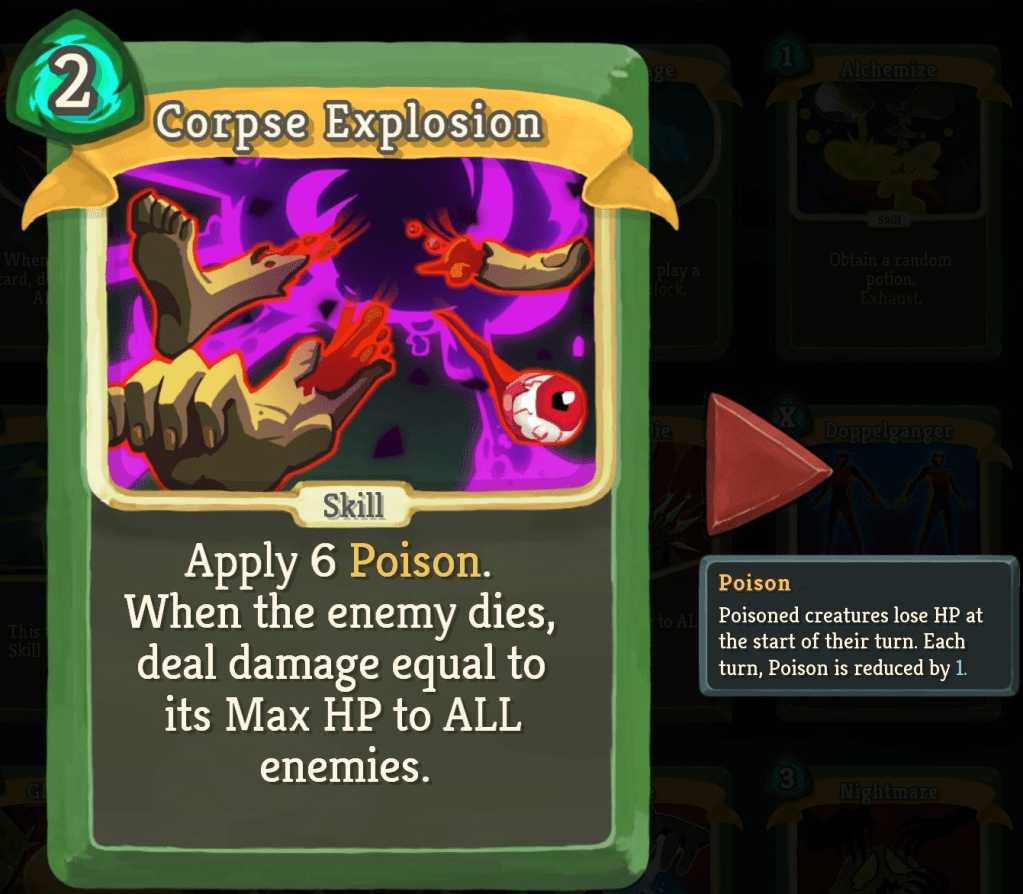

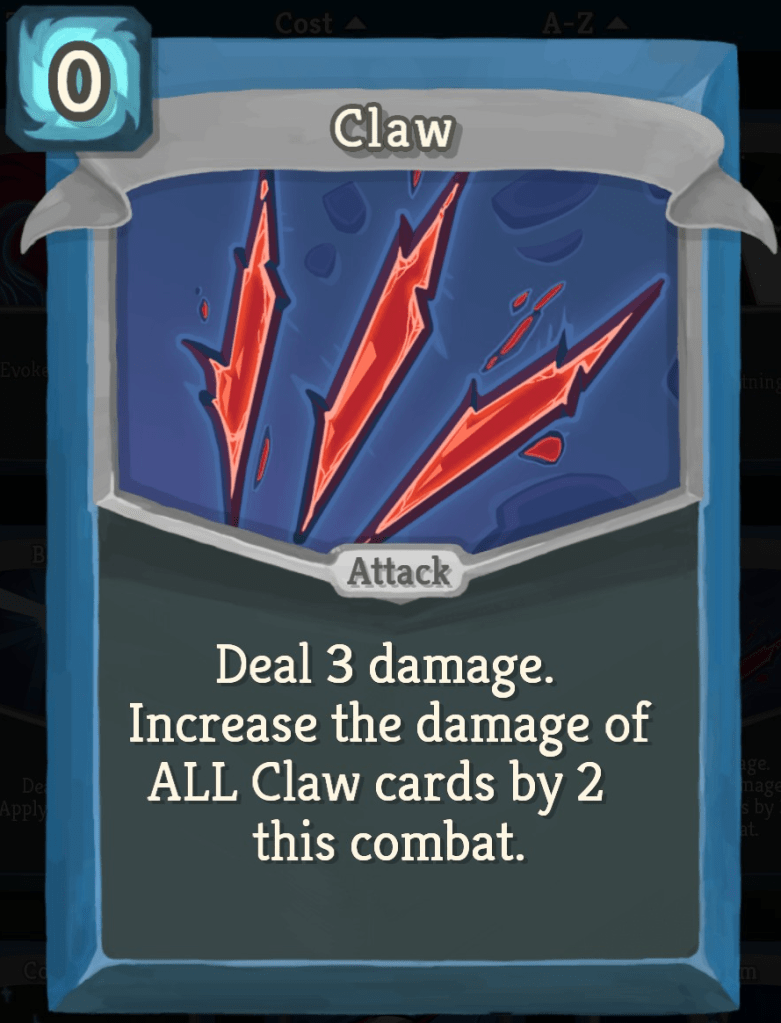

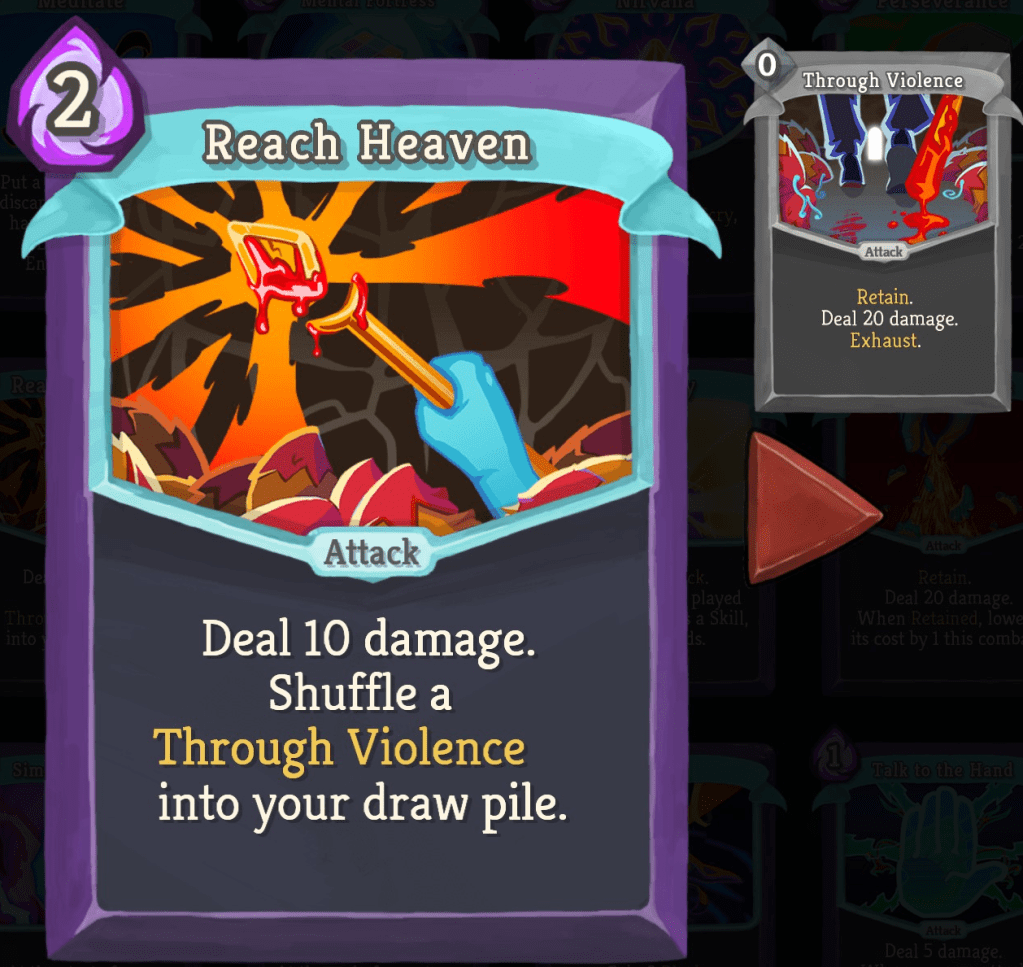

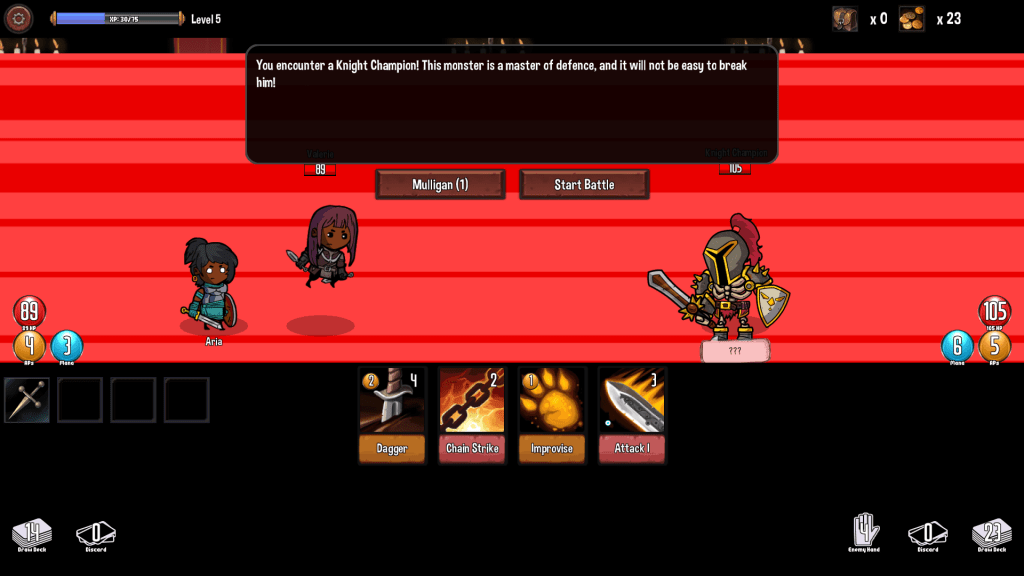

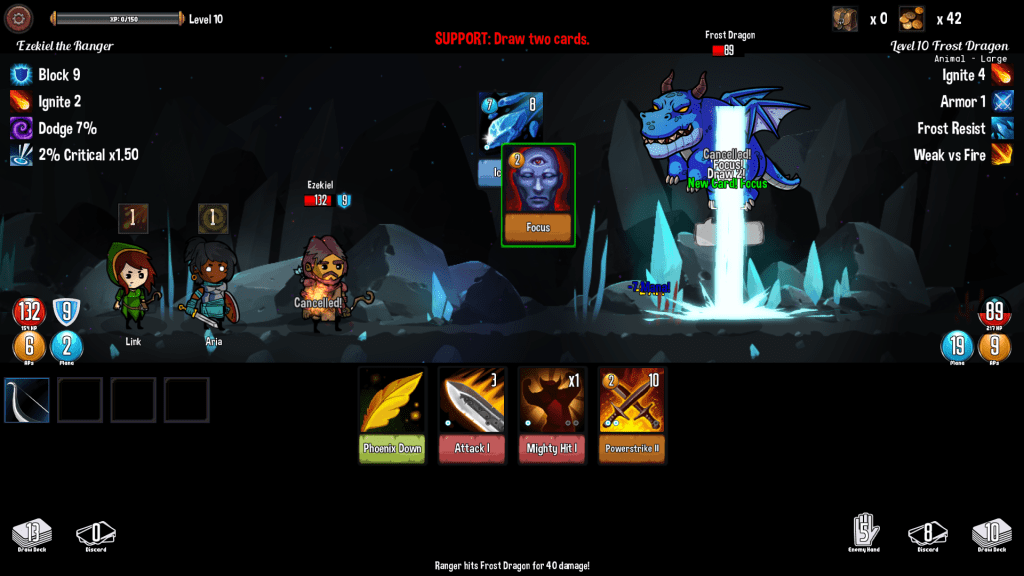

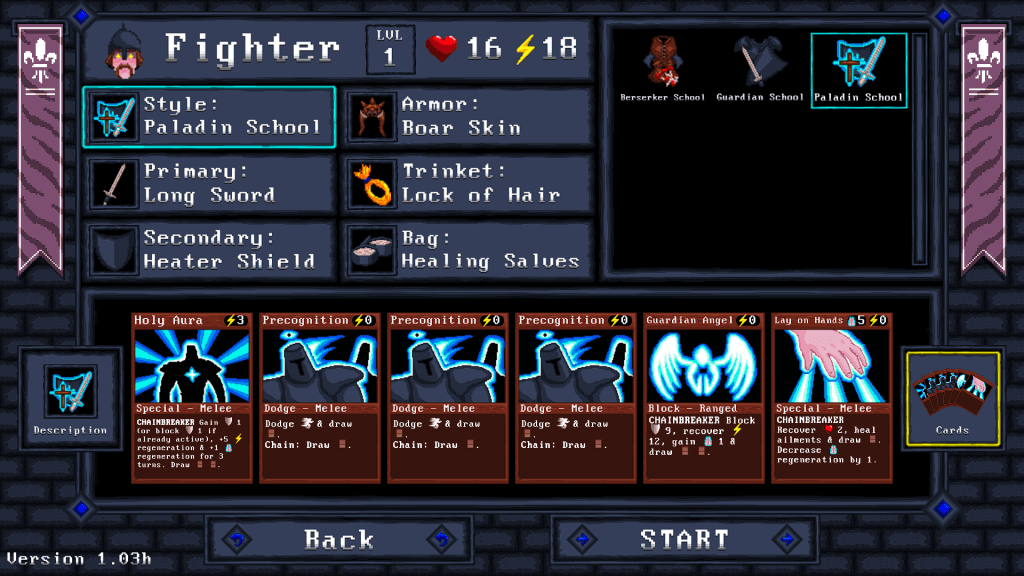

The card design and artwork is nothing short of phenomenal. This is what every card-based computer game should aspire toward. Clear, legible, tonally appropriate fonts. Mechanics that can be clearly understood as keywords, and cards that can be moused over to bring up a tooltip for a reminder of what those mechanics are. Cards that rarely contain more text than 15 words. Artwork that reduces nicely to smaller displays and retains legibility. It’s all here, it’s all textbook. For a laugh, if you want to see how important good artwork can be to these games, it is possible to unlock and switch to ‘beta art’ cards that look more like the MS Paint-style cards of Dream Quest. A bit of credit is due to the UI as well: if you haven’t played it, these screenshots likely look extremely busy, but in a game with a lot of stockable and stackable mechanics, the icons, counters, and timers are very easily read and understood without being intrusive.

Closing Remarks

Slay the Spire could be both the starting and end point of your exploration into the little corner of gaming that is the roguelike deck-builder. (Obviously, I would hope you would stick with me a little longer, but you’d get the majority of all you’d need to know here!) Here’s a story that’s just about the most ringing endorsement I can give it. A year or so ago I was recovering from deviated septum surgery, which is where they basically widen one of your nasal cavities to help you breathe. Really, I should have just tried to sleep as much as possible, because staying awake through two nostrils full of constantly bleeding gauze is something you want to be awake for as little as possible. I had a Switch full of major releases I hadn’t started and an e-book full of unread stuff that this would have been the perfect opportunity to catch up on. Instead, I bought a second copy of StS for my smartphone and just started from the beginning. The hours melted away for next few days. It did a far greater job of keeping the constant discomfort out of mind than the copious painkillers.

Less anecdotally, StS could be the perfect gateway into the broader genre of CCGs without the hassle of buying physical cards and tracking down people willing to teach you the basics. The mobile/online versions of the big names like Magic and Yu-Gi-Oh! leave a lot to be desired for a number of reasons, and exist mostly to hook people into their respective franchises rather than serving as spaces for people to get a feel for if the genre is ‘for’ them in the first place. When you buy StS, there are no booster packs or metagame mechanics to worry about. Immediately accessible, easily understood, infinitely enjoyable. A credit to videogames.

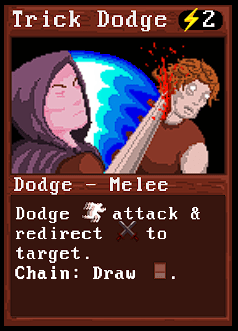

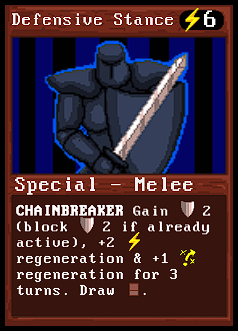

Standout Cards

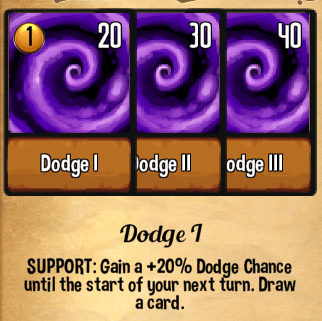

When I said earlier that this is a tightly designed game, one example is that you can actually feel the rigorous playtesting throughout. There aren’t a million cards in it, and most of them only do two things at most, but they are extremely well-considered and versatile puzzle pieces. YouTube has countless tier lists of what experts consider the best cards to be, with a surprising lack of consensus. This suggests a remarkable balance that caters to a wide range of playstyles. With that in mind, here’s one I like for each of the four classes: