UPDATE (Nov 18th, 2023): In celebration of the game’s 10th anniversary, I interviewed the game’s developer, Greg Lobanov, which you can click here to watch or see at the bottom of this post.

There isn’t a ton of material out there making claims as to what the ‘first’ roguelike deck-builder may be. This Verge article points to Peter Whalen’s 2014 mobile game Dream Quest (as “the “watershed” moment for the modern iteration of the genre”. Likewise, Joshua Byer’s Game Design Deep Dives: Roguelikes submits that “Dream Quest is viewed by many as the progenitor for deck-building roguelikes.” As an original game that explicitly combines card deck-building with randomised adventure elements, it seems fairly sound to call Dream Quest the first of its kind. We’ll be looking at it in the next post. However, it isn’t isn’t quite the oldest game that meets my criteria.

According to data trawlers SteamDB and Steamspy, the earliest released game with the tag ‘Roguelike Deckbuilder’ is a game called Coin Crypt, developed by Greg Lobanov and released through Steam Early Access on November 18th, 2013. There may yet be something before this that meets my rules and either didn’t receive a Steam release or slipped through the cracks of my search engine hunt. Nevertheless, I feel fairly confident in taking Coin Crypt as a starting point and will happily entertain debate on alternatives. (Not to get into the weeds here, but sometimes I wonder how many hobbyist prototypes, unfinished demos, or notebook ideas of things we would now recognise as a roguelike deck-builder may be out there that predate Coin Crypt.)

Premise and Gameplay

Somewhere in the Pacific, the lost ruins of a ‘coin civilisation’ have been uncovered, luring ‘lootmancers’ to do battle in a bid for the ultimate treasures at their highest peaks and deepest depths. The Rogue influence is readily apparent in Coin Crypt’s overworld. In a single run, players traverse several worlds divided into three randomised stages occupied by enemies, shopkeepers, and hidden secrets. Coins are required to do almost anything – they function as your battle actions, currency, and health. Using up all your coins is a lose condition akin to ‘decking out’ in a physical CCG, immediately ending the run. Funnily enough, you can also defeat enemies like this, although doing so means you won’t win those coins as loot. Coins aren’t just single-use in battle, they’re single-use for good – so keeping your deck (purse?) topped-up while being careful not to fill it with turn-wasters is paramount.

The one-on-one battles play out similarly to Active Time Battles in the Final Fantasy series – turn-based, but with factors affecting how quickly and often those turns come about for both sides. Once selected, some coins take longer for their effect to trigger than others. You can only draw a few coins from your ‘deck’ into your hand each round, and you must work out which one to play ASAP. Fast choices minimise damage and maximise loot from foes. Multiple coins can be played simultaneously if you draw more than one of the same kind, and you can forfeit a turn for a redraw if you’d rather save certain drawn coins for another time. This may sound like an awful lot to be keeping track of, but it makes for very short, addictive battles that demand good, quick decision-making that anticipates future moves or even battles.

Failed runs reward players by allowing them to redeem the total value of coins gained during their run for new character classes, and there’s a lot of them: 20 classes to the base game and 7 in the one DLC package, Sea and Sky, which also adds new overworld areas and rewards. Granted, their individual differences do not always completely transform playstyles in the way the four Slay the Spire classes are so different from one another, and the game’s difficulty is radically altered by who you pick. Still, there’s a lot of novelty and challenge to be had – I find myself drawn to the Assassin, who hits hard but can’t heal well, and the Wizard, who regains multiple copies of coins used in battle but also simultaneously loses ones at random from their deck.

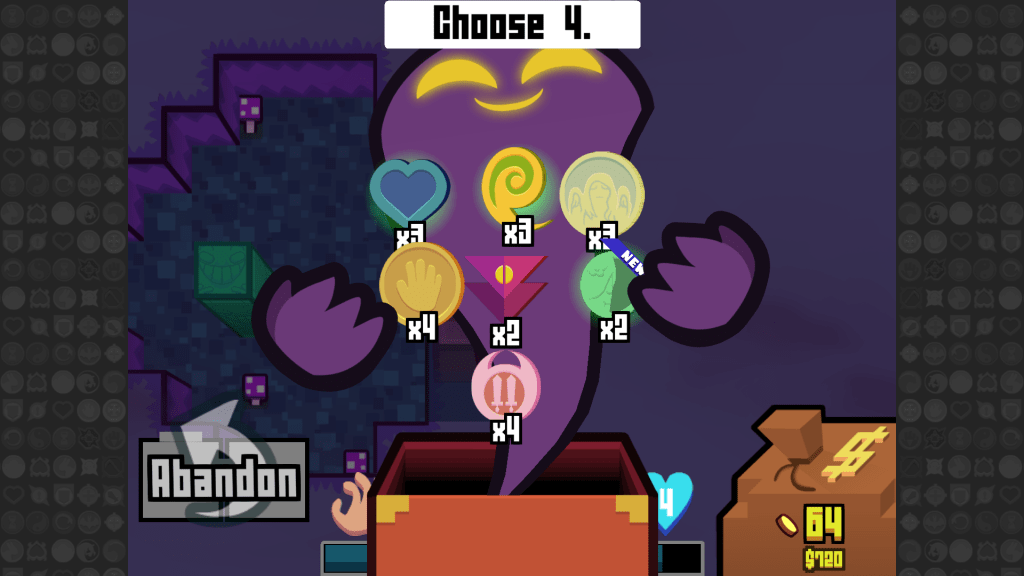

An admission – I love this genre, but I’m not very good at it! It took me 10 hours to even beat the game once, and even then with a non-standard class (the Wizard) using an alternative coin bag (one that makes you likelier to pick up damage-dealing coins). In that time I unlocked every character class you can with coins from failed runs. Nevertheless, I feel it fair to say that the game is a little cryptic (ha!) about some of its mechanics. For one, you can offer coins to deities, who in return will grant you certain coins or debuff enemies. I completely ignored them for my first several runs because I was more concerned about loss by deck-out, unaware that they were buffing later enemies in anger for my lack of piety. Shop items often seem very expensive given that coins are also your literal lifeblood. Lastly, the ‘blessing’ system, which gives you a selection of buffs that always come with a debuff, almost always felt too punitive to risk using. Which of these are balancing or difficulty curve failings and which of these are just my own ineptitude will vary by the player, of course. Whether these mechanics enrich or frustrate is one thing, but they will be a part of the decision-making in every run, so they bear mentioning.

Randomised Elements

Besides enemy and loot chest placement, the levels of Coin Crypt are made up of randomly put-together hallways and rooms. Players have some decent agency in their exploration. If you want to make a mad dash for each level’s exit, losing as few coins on the way as possible, you can do that. If you feel like your coin build benefits from fighting everything you come across, you can do that, too. If you’re able to unlock certain barriers, you can even take alternate paths to plumb the ruins’ depths rather than scale their heights, leading to different enemies, coins, bosses and so forth. On the other hand, the randomisation sometimes led to my runs ending long before they ever even got off the ground, and when a run started going south, I rarely felt able to delay failure for much longer. I’m not sure if this is an overdependence on random number generation to draw good coins or if certain classes just have a harder time building up steam than others, but it was rarely so discouraging a loss that I didn’t want to jump right back in.

Presentation

So yes, some minor issues, but the compulsion inherent to the gameplay loop is very powerful and is reflected in the sound and visuals. There’s a palpably sweet tension in choosing a coin and hoping it pops off before the enemy’s, and the accompanying sound effects of a bunch of loot being dropped into your bag upon victory (essentially extending a time limit on your survival) brings relief. Seeing the little ‘NEW!’ tag next to a shiny coin you haven’t seen before satisfies the primate brain, as is then immediately weighing up whether or not it plays nicely with everything else you’re currently rolling with.

The colours and UI elements are bold and bright. In a world of mostly cuboid elements, the coins are a real standout – there is intrinsic satisfaction in seeing the not-actually-3D coins in your deck spinning around. The hard edges and flat colours can lose their flavour after a while, but the hand-drawn character and enemy art gives the game’s visual elements a certain unity and timelessness. Also, being able to directly WASD-key your character around RPG-style rather than simply clicking on waypoints between scenarios is very involving, especially if you really can’t afford to get into a fight when you’re bleeding coins.

An aside on the coin design. Unlike most games in this genre, taking your time with your movemaking is actively discouraged, so being able to identify what each coin does the instant it gets drawn is very important. Coin Crypt’s solution is to have the shapes, iconography and colours of the coins broadly reflect what they do. Damage-dealing coins, for example, will generally either be red in colour, have spiked edges, or feature a sword icon. Healing coins are typically blue or feature cross-shaped edges or icons. More exotic damage or healing coins may only feature one or two of these elements, but as long as you recognise one of them immediately it should give your brain the quick hint it needs to recall what it does. With 201 coins to the base game and another 100 in the DLC, they don’t all perfectly follow an internal consistency (as attested to by this ‘coin encyclopaedia’) but I rarely found myself totally stumped by what a coin did upon drawing it. Unfortunately, in the instances I did forget what a coin did in battle, I found that the reminder tooltips could sometimes get obscured by other rapidly-changing UI elements when you hover over them – not ideal in the middle of a frantic battle that could be your last. Regardless, the point I’m striving for here is that many roguelike deck-builders can consider the art that comes with their cards to be a luxury or visual afterthought to their gameplay utility. For Coin Crypt, the coin design is integral to its playability.

Closing Remarks

These retrospectives are not intended to be reviews, but I would like to encourage people to try out the ones I enjoy as I go along. Coin Crypt‘s sheer combat speed alone makes it worth seeing if it’s something you like. The compulsion to always be casting coins removes the indecision paralysis that sometimes puts people off card games. While its systems and synergies are a bit opaque for your first several runs, you will eventually find a handful of classes or strategies you enjoy that bring you closer to endgame runs if you stick with it. (Also, I’m stunned it isn’t available on mobiles – the large coins and mouse-click-navigable environments at times make it feel like it was designed from the ground-up for such a thing!)

Standout Cards

An ongoing closing feature I’ll include here will be cards (or in this case, coins) that have stuck with me for whatever reason during my time with the game. These aren’t my suggestions for the best cards, simply ones that may have served me well, are cosmetically interesting, or have some other noteworthy quality.